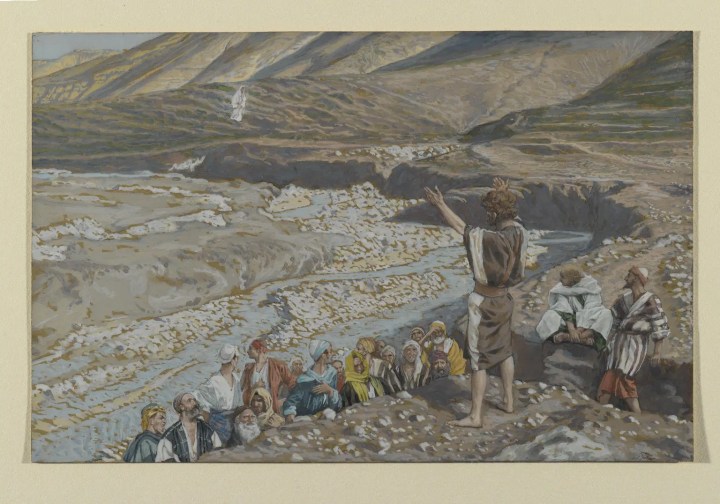

One of the loveliest aspects of Christian Worship is how many of the words we use in worship are taken from the Bible. Whenever the Eucharist is celebrated, we pray to God using the words of John the Baptist which are heard in the Gospel today:

‘Look, there is the Lamb of God that takes away the sin of the world!’

‘Dyma Oen Duw sy’n cymryd ymaith bechod y byd.’ (Jn 1:29)

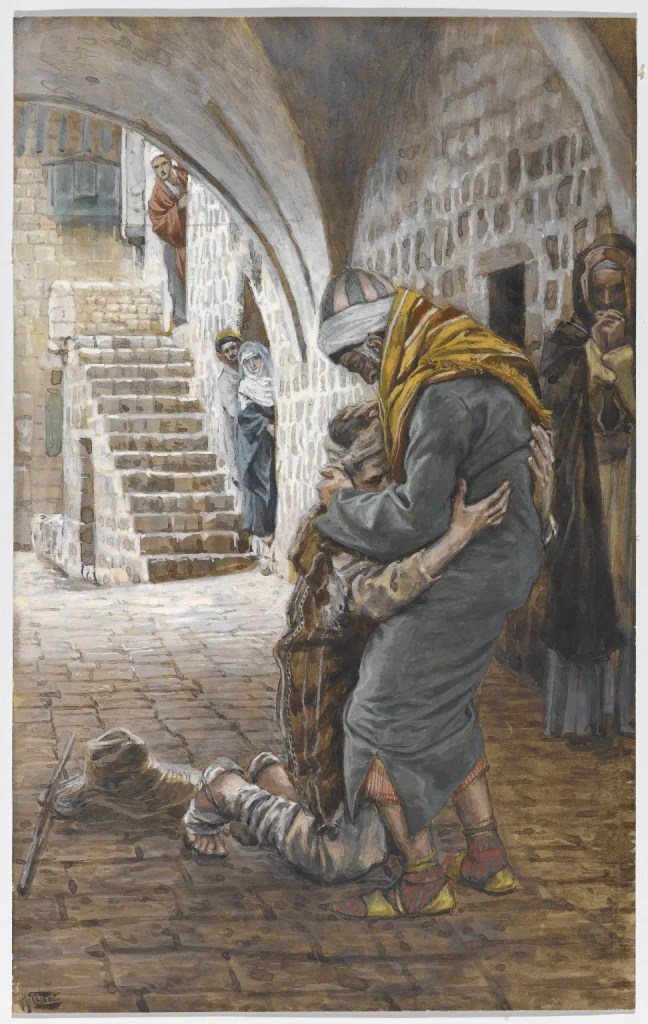

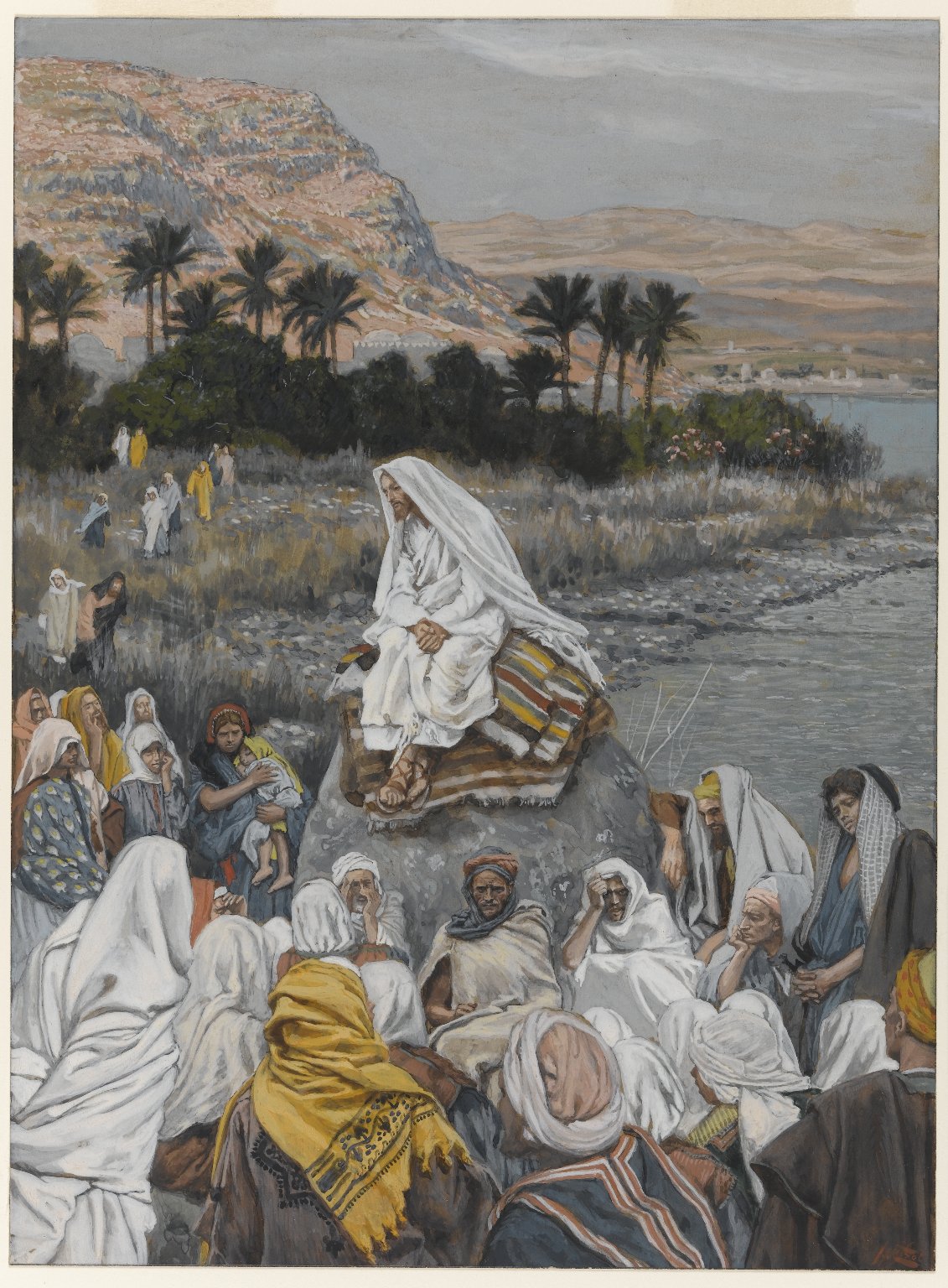

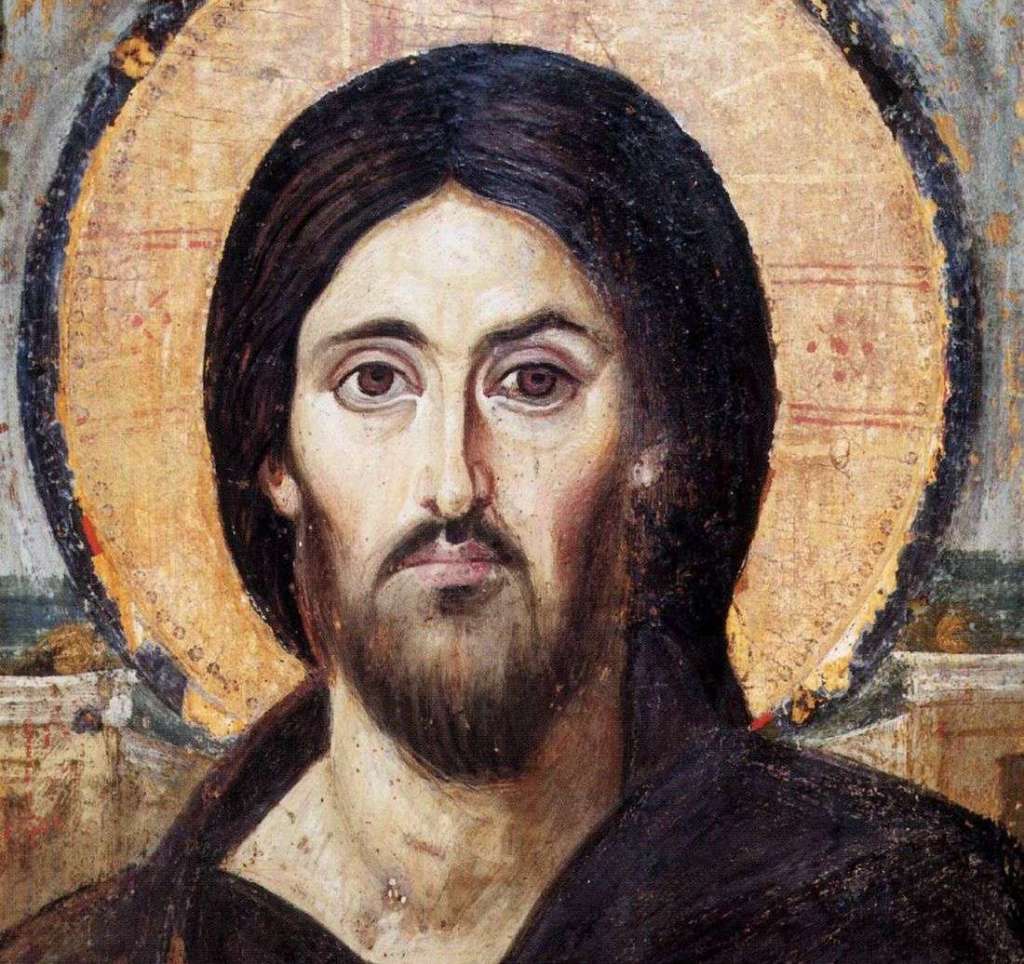

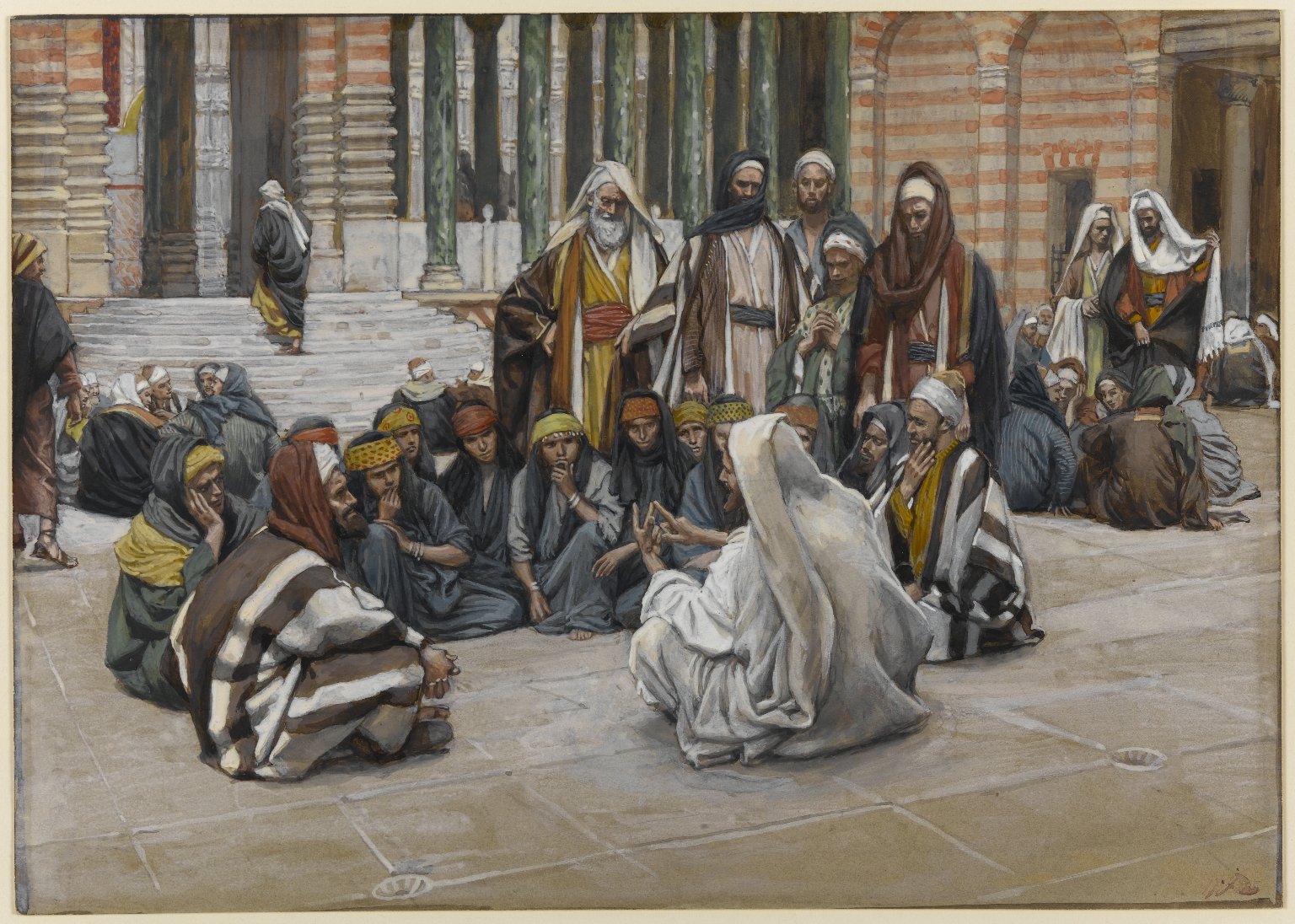

John speaks these words at the beginning of Jesus’ public ministry, after Our Lord’s Baptism and before the calling of the first disciples. John the Baptist has invited people to repent, to turn away from what separates them from God and each other. John’s mission finds its fulfilment in Christ, whom he has just baptized. Jesus is the person who reconciles God and humanity, through His death on the Cross. This is the Good News of the Kingdom. We are loved by God, who flings His arms wide on the Cross to embrace the world with love. Our Divine Creator embraces shame and torture, to show the world love. It isn’t what you would expect, and that is the point. God experiences human pain and suffering and in doing so makes a relationship possible, so that we might come to know Him, and to love Him.

John then explains Jesus’ importance:

“This is the one I spoke of when I said: A man is coming after me who ranks before me because he existed before me.” (Jn 1:30)

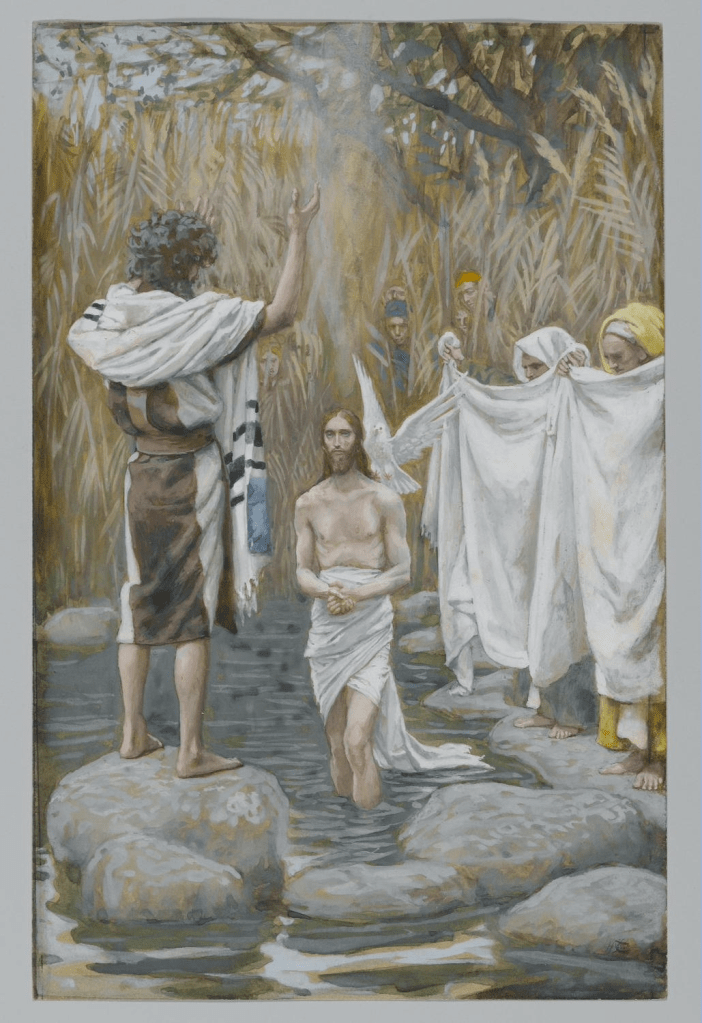

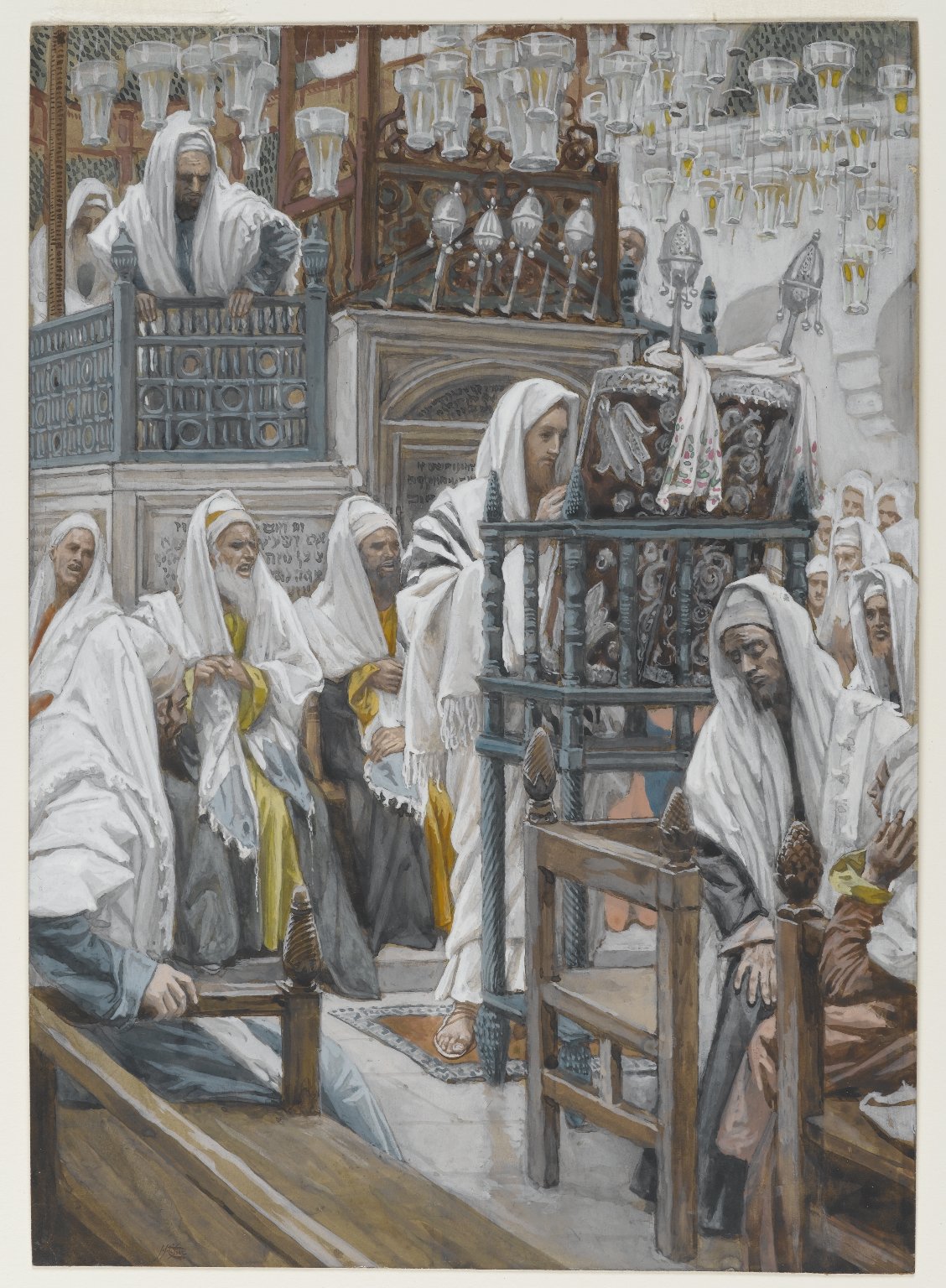

We know from Luke’s Gospel that John is six months older than Jesus, so what does the Baptist mean by this? How can Jesus have had life before John? The reason is that Christ is God Incarnate, He has always existed, and the Eternal has taken flesh in the womb of His mother, Mary. John then bears witness to the numinous events that occur when he baptizes Jesus:

“I saw the Spirit coming down on him from heaven like a dove and resting on him. I did not know him myself, but he who sent me to baptise with water had said to me, “The man on whom you see the Spirit come down and rest is the one who is going to baptise with the Holy Spirit.” Yes, I have seen and I am the witness that he is the Chosen One of God.” (Jn 1:32-34)

At Jesus’ Baptism we see and hear the Three Persons of the Holy Trinity. God the Father speaks, the Son is obedient, and the Spirit encourages. Jesus will pour out the Holy Spirit, the bond of love between the Father and the Son, the agent of healing and reconciliation. John recognises that Christ is the Son of God, and proclaims this truth: that God dwells with His people, and has come to save them.

The fact that John describes Jesus as ‘The Lamb of God’ is consequential. Lambs were a central part of the Jewish festival of Passover. In order to avert the tenth plague in Egypt, the people of Israel were told to take a young lamb without any blemish and slaughter it. They were then instructed to anoint the doorposts of their houses with the lamb’s blood, so that their firstborn would be saved, and would not be killed by the Angel of Death. The lamb was to be roasted over the fire and eaten standing up whilst dressed ready for a journey. This festival of Passover is the high point of the Jewish religious calendar, and commemorates the start of their journey from slavery in Egypt to the Promised Land of Israel. It is also the time of Jesus’ Passion, Death, and Resurrection.

In order to meet the requirements of the large number of people celebrating the passover festival in the early 1st century, there needed to be a lot of shepherds raising flocks of animals for slaughter. In the Christmas story we see that the first visitors to the Holy Family in Bethlehem were local shepherds. As Bethlehem is only six miles from Jerusalem, these shepherds were raising the thousands of lambs that would be consumed at Passover in nearby Jerusalem. Jesus, like these lambs, was also without blemish, and would be killed at Passover. So from the very moment of Christ’s birth, His Sacrificial Death is foreshadowed.

Traditionally Jesus’ death is understood to have taken place at the ninth hour, that is 3pm. Significantly, this is the same time that the passover lambs began to be slaughtered in the Temple in Jerusalem for the Passover feast. This is not mere coincidence, but rather signal proof that Christ’s death is sacrificial, and also represents the new Passover, bringing freedom to the people of God. By describing Jesus as: ‘the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world’. John understands that Jesus is the Passover Lamb, whose death will save us all.

The image of a lamb also brings to mind a passage in the prophet Isaiah, where the Suffering Servant is compared to ‘a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and like a sheep that before its shearers is dumb’ (Isa 53:7). This prophecy will be fulfilled in Holy Week on Good Friday, and also every time the Eucharist is celebrated. This is the beginning of the community of believers to which we belong through our faith and through our baptism. We, like the Christians in Corinth to whom St Paul wrote, are:

‘those sanctified in Christ Jesus, called to be saints together with all those who in every place call upon the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, both their Lord and ours.’ (1Cor 1:2)

We can call upon Christ’s name in prayer because He loves us, and saves us from our sins. From the beginning of Jesus’ ministry, even from the gifts offered by the Three Wise Men, Our Lord’s life and mission is to be understood in terms of the death He will suffer. It is this sacrificial, self-giving love which God pours out on His World, which streams from our Saviour’s pierced side, and which makes our peace with God, and with one another. It is this recognition of who and what Jesus really is that enables us to recognize who and what we really are. By following Christ’s teachings and example we can live our lives truly, wholly, and fully. Loved by God and loving one another.

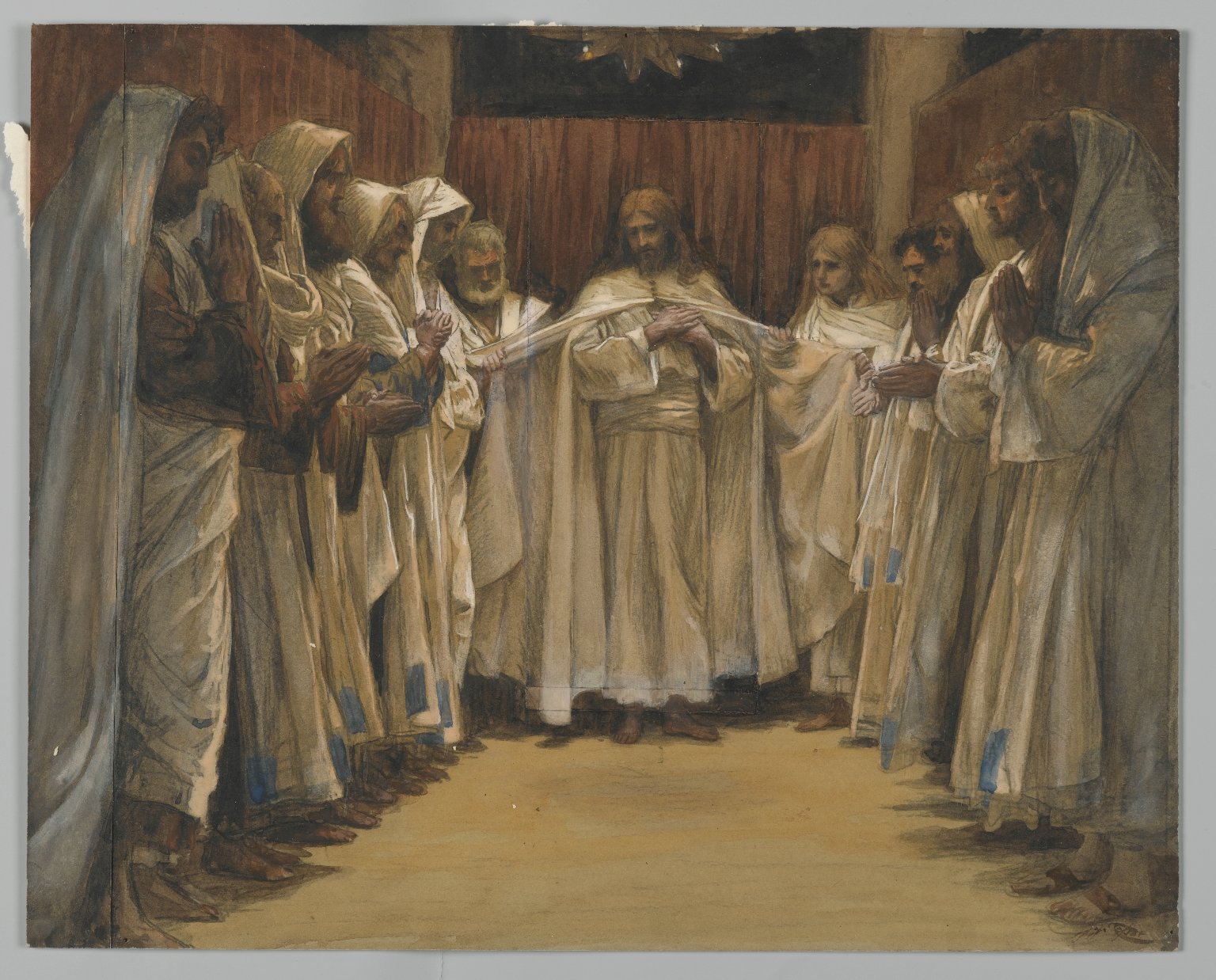

Together, we can express this love most profoundly when we celebrate the Mass together, because the Eucharist is the sacrament of unity. This Sacrament unites heaven and earth through the sacrifice of Calvary, and allows all humanity to share the Body and Blood of Our Saviour Jesus Christ. We feed on Him so that we may become what He is. This enables us to share eternity with Our Lord, and to live lives full of faith, and hope, and love. So then, let us lift up our hearts and give thanks for Jesus, the Lamb of God. Let us enter into the mystery of God’s self-giving love. And let us join together to give glory to God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit, Duw Dad, Duw y Mab a Duw yr Ysbryd Glân. To whom be ascribed all might, majesty, glory, dominion and power, now, and forever.