I would like to begin today with some words of Pope Benedict XVI: Today the Church celebrates Ash Wednesday, the beginning of her Lenten journey towards the great festival of Easter. The entire Christian community is invited to live this period of forty days as a pilgrimage of repentance, conversion and renewal.

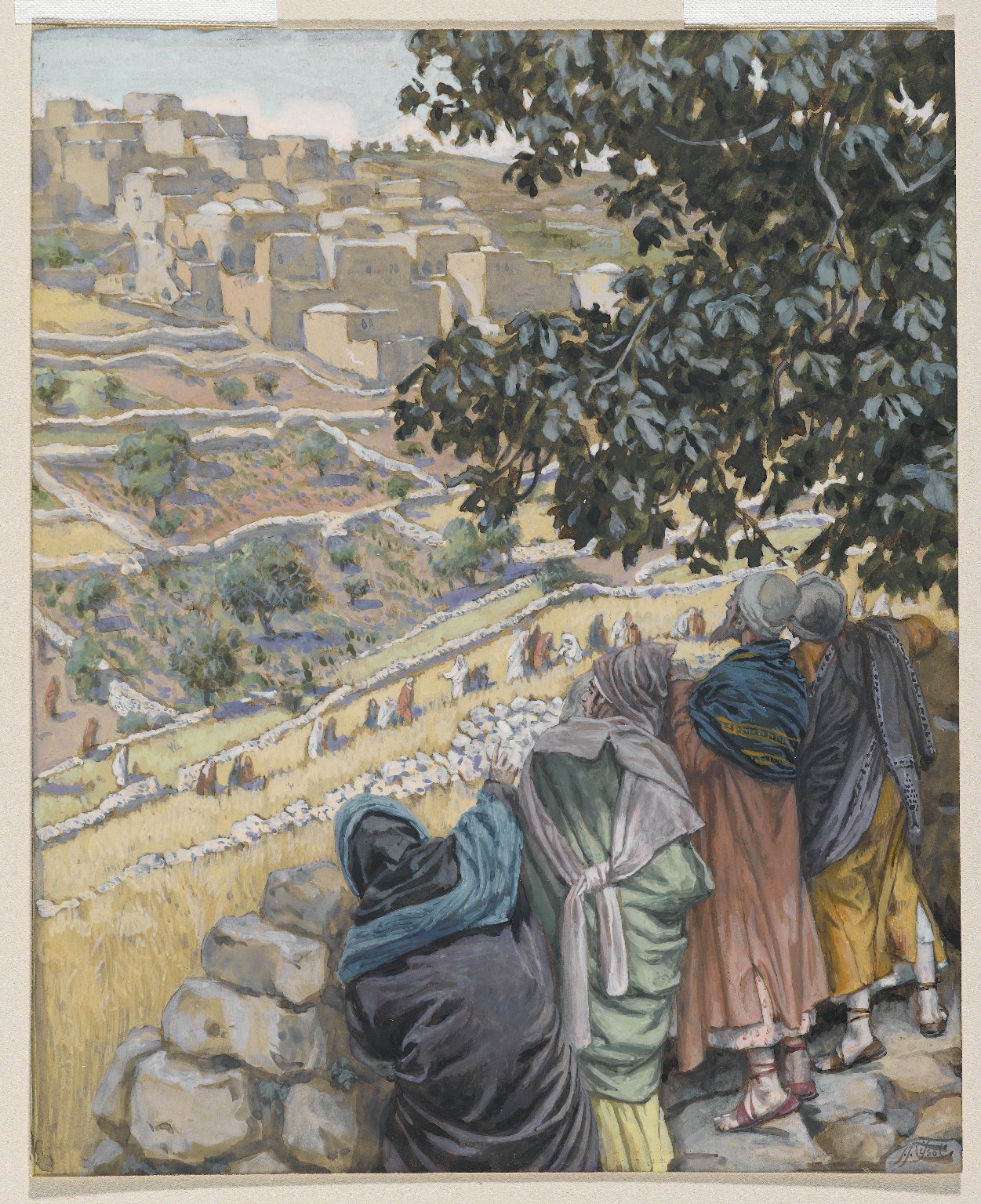

In the Bible, the number forty is rich in symbolism. It recalls Israel’s journey in the desert: a time of expectation, purification and closeness to the Lord, but also a time of temptation and testing. It also evokes Jesus’ own sojourn in the desert at the beginning of His public ministry. This was a time of profound closeness to the Father in prayer, but also of confrontation with the mystery of evil.

The Church’s Lenten discipline is meant to help deepen our life of faith and our imitation of Christ in his paschal mystery. In these forty days may we strive to draw nearer to the Lord by meditating on his word and example. We seek to conquer the desert of our spiritual aridity, selfishness and materialism. For the whole Church may this Lent be a time of grace in which God leads us, in union with the crucified and risen Lord, through the experience of the desert to the joy and hope brought by Easter. [Pope Benedict XVI Catechesis at the General Audience 22.ii.12:

http://www.news.va/en/news/pope-conquering-our-spiritual-desert ]

Today we begin our journey with Christ into the desert for forty days. Deserts are places of lack and isolation, something which we have all experienced over the last few years. Not long ago we were cut off from people, places, and things we are accustomed to do because of the pandemic. In many ways those two years felt something like a continual Lent. This year, as every year, as Christians, we thoughtfully prepare to celebrate the Passion, Death and Resurrection of Jesus Christ, who began his public ministry after His Baptism by going into the desert.

To go into the desert is to go to a place to be alone with God, in prayer, to face temptation, and to grow spiritually. It is something which Christians do together over the next six weeks or so, to draw closer to Jesus Christ. By imitating Him, and listening to what He says to us, we prepare ourselves to enter into and share the mystery of His Passion, Death, and Resurrection; so that we may celebrate with joy Christ’s triumph over sin and death, and His victory at Easter.

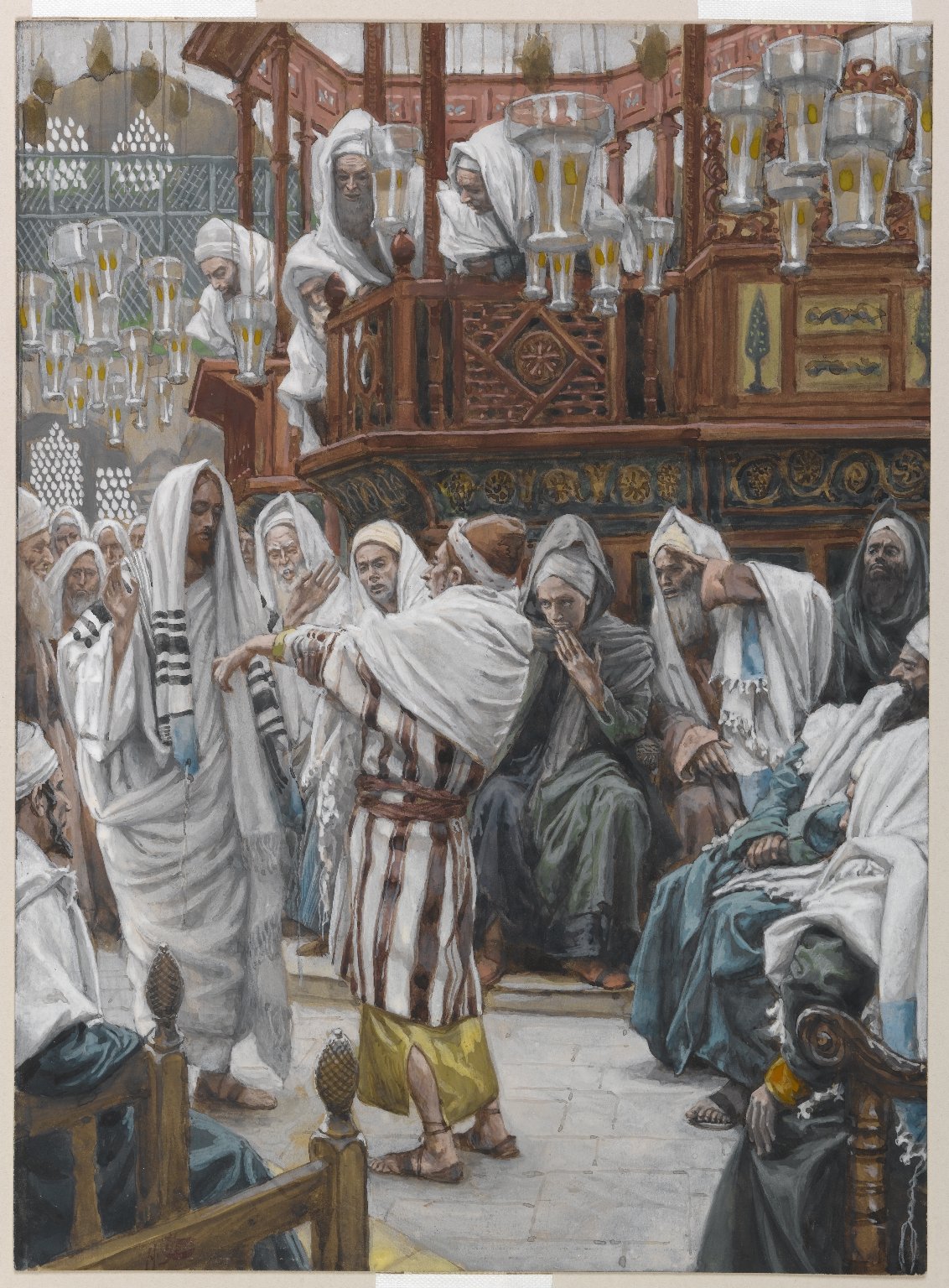

In the Gospel reading today, Jesus teaches His disciples how to fast. The point is not about making an outward show of what we are doing, but rather about how the practice affects our interior disposition. This is clear from the first reading, from the prophet Joel, who gives this advice:

“Yet even now,” declares the Lord, “return to me with all your heart, with fasting, with weeping, and with mourning; and rend your hearts and not your garments.” Return to the Lord your God, for he is gracious and merciful, slow to anger, and abiding in steadfast love; and relents over disaster. (Joel 2: 12-13)

Through the prophet, God is calling His people back to Himself, in love and mercy. Rather than the outward show of mourning through the tearing of our clothing, we are instead instructed to open our hearts to God, so that He can heal us. However, we can only find healing if we first recognise our need for healing, and understand that healing is something that only God can do for us. We cannot bring it about ourselves.

Human beings, by nature, like to show off, to engage in display, and to tell people about things. Yet in the Gospel today, Christ tells us to do the exact opposite. We are told not to show what we are doing, for our Lenten disciplines. We are to keep them hidden. This is completely in line with the advice of the prophet Joel that fasting, like mourning, has an interior quality which is important.

By giving up something we love and enjoy, and regulating our diet we are not engaging in a holy weight-loss plan. What we are doing is training our bodies and our minds, to be disciplined. Through these actions we express physically the radical purification and conversion which lies at the heart of the Christian life: we follow Christ.

We follow Christ into the desert. We follow Christ to the Cross, and beyond, to be united with Him, in love and in suffering. In this we should bear in mind St Paul’s words to the Church in Corinth that we are called to suffer with and for Christ, to bear witness to our faith, and to encourage people, as ‘ambassadors for Christ’. This starts with our reconciliation with each other, and God’s reconciliation and healing of each one of us. Just as for any other role we undertake in life, it requires preparation.

The Gospel talks of three ways to prepare ourselves: Firstly, Fasting: disciplining the body, and abstaining from food. Secondly, Prayer: drawing closer to God, deepening our relationship with Him, and listening to what He says to us. Thirdly, by Charity, or Almsgiving: being generous to those in need, as God is generous towards us, is to follow Christ’s example. Matthew’s Gospel clearly states that we do not do these things in order to be seen to be doing them — in order to gain a reward in human terms, of power or prestige — but to be rewarded by God.

We should always remember that as Christians we cannot earn our forgiveness through our works. God forgives us in Christ, who died and rose again for us. We plead His Cross as our only hope, through which we are saved and set free.

Being humble, and conscious of our total reliance upon God, allows us to be transformed by Our Heavenly Father, into what He wants us to be. God’s grace transforms our nature, allowing us to come to know and to live life in all its fulness. This is the joy of the Kingdom, and a foretaste of Heaven. Through grace we are united with God, and know and experience His love and forgiveness. We are transformed by Him, into His likeness, sharing His life and His love.

Let us, therefore, use this Lent, to draw ever closer to God and to each other. Through our fasting, prayer, and charity, may we be built up in love, and faith, and hope. Let us prepare to celebrate with joy the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ. To whom, with God the Father, and God the Holy Spirit, gyda Duw y Tad, a Duw yr Ysbryd Glân, be ascribed all glory, dominion, and power, now and forever. Amen.